About Ball Park Baseball™

BALL PARK BASEBALL™

A Tabletop Review

Eric Scherpf, The Sports Games Journal, March/April 2007

Reprinted with permission

Ball Park Baseball is a tabletop simulation developed in the late 1950s by Charles Sidman, now a retired professor, with input from some of his colleagues at Kansas University and, later, according to Mr. Sidman, even from baseball numbers guru Bill James (by his own account, James would play Ball Park in a Lawrence, Kansas establishment named after the game). Ball Park has undergone some significant enhancements over its long history, perhaps most notable of which was the addition of separate bases empty/runner on split columns. This addition no doubt greatly improved overall statistical accuracy, in addition to making it possible to more closely replicate pitchers’ ERA and a batters’ RBI totals.

Ball Park is still being published by Mr. Sidman, in Gainesville, FL. Every team (and corresponding ballpark chart) from 1901 to the present (plus 1894) is available for a la carte purchase; in other words, you can buy as many or as few teams as you like without having to purchase an entire season set. However, the game is not exactly cheap. Each team costs $3 and each park chart costs $1. Park charts are generally updated only when a park undergoes a renovation that alters the ‘way it plays,’ so you very seldom have to purchase a new chart for the same park. Mr. Sidman does not currently maintain a website for his game, so all payments must be made via snail mail with either check or money order. Mr. Sidman will send out a free informational brochure, along with an order form, upon request (bpbaseball@gmail.com).

Ball Park is still being published by Mr. Sidman, in Gainesville, FL. Every team (and corresponding ballpark chart) from 1901 to the present (plus 1894) is available for a la carte purchase; in other words, you can buy as many or as few teams as you like without having to purchase an entire season set. However, the game is not exactly cheap. Each team costs $3 and each park chart costs $1. Park charts are generally updated only when a park undergoes a renovation that alters the ‘way it plays,’ so you very seldom have to purchase a new chart for the same park. Mr. Sidman does not currently maintain a website for his game, so all payments must be made via snail mail with either check or money order. Mr. Sidman will send out a free informational brochure, along with an order form, upon request (bpbaseball@gmail.com).

I have found this game to be quite a "hidden gem" among baseball simulation board games. A brilliant and unique aspect of the game design is the interaction of fielding skill and ballpark effects. Park effects in Ball Park may be the most comprehensive of any game, as each park is rated not only for its home run factor (to all three fields) but also for its singles, doubles, triples and error factors, separately for the infield and the outfield. Thus, the value of an outfielder with excellent range will be greater in, say, the spacious outfield of Coors Field or the Metrodome than in one of the smaller parks.

What may initially strike newcomers to the game as somewhat simplistic is the use of a single, composite fielding rating, rather than the usual separate range and error ratings. The nine fielding ratings reflect, essentially, three range categories and, corresponding to each range category, three error categories. It appears, however, that each error category differs slightly across range ratings, so that the high-error category associated with a fielder with excellent range will not be exactly the same as the high-error category associated with a fielder with poor range (i.e., the latter will tend to be more error prone). The home park’s error factor and the distribution of chance plays, by position, on pitchers’ cards further refine fielders’ error tendencies. A 1949 New York Yankees replay on the game’s Delphi forum shows that, after 100 games, team errors (89) project to the precise number of errors actually committed by the 1949 Yankees (137).

Another rather unique and well-conceived aspect of the game is its multi-layered base running system, which yields interesting and detailed outcomes for an array of different types of hits. For instance, a single can result from a regular single, a long single (which could be stretched into a double), a sharp single, a Texas Leaguer, and an infield hit, each with different consequences for runner advancement. Chance plays, requiring a park chart reference, include a tapper, a smash, a hard (or difficult) chance, a short fly, a drive and a long fly ball. Batters can hit a pop out to the outfield, the aforementioned short fly and long fly, a medium fly, a (line) drive, and a deep fly. Again, each result has different consequences for runner advancement after the catch. Also incorporated into the base running system is the occasional wild play on the base paths.

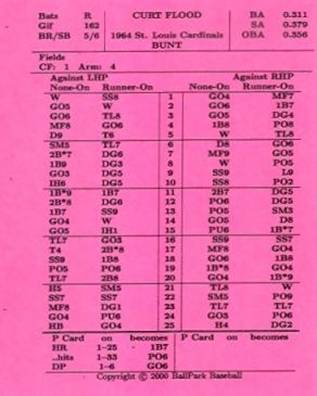

The pitcher and batter cards have distinct results for vs. left and vs. right situations, as well as for runner(s) on and bases empty situations. These four split columns on each player's card, along with the many chance plays that are possible, allow Ball Park to achieve a fine degree of accuracy that one might not expect from a game that uses a 1-50 chance mechanism. The cards are also designed to replicate batters and pitchers’ ground ball to fly ball ratios as well as their tendencies to hit, or induce balls to be hit, to certain fields. The separate columns for bases empty and runner on situations incorporate, in a natural way, a batter’s ability to hit in the clutch as well as a pitcher’s ability to pitch out of a jam.

Ball Park makes extensive use of “controls” on the player cards that allow it to overcome an inherent shortcoming of the 50/50 game engine. Players with extreme statistics that cannot be reflected on their card alone will be able to control outcomes on the opposing pitchers/hitters card. This would apply, for example, to pitchers who yield an unusually low rate of walks or home runs. Controls are also employed for batters who have extremely low home run, walk, or strike out tendencies, as well as those who ground into very few, or very many, double plays. Controls are also used to properly replicate players with extreme vs. LH/RH platoon splits.

Mr. Sidman originally designed Ball Park as a game to be played against a live opponent. That is not to say, however, that it is not suitable for solitaire play. Ball Park offers each manager an impressively realistic range of strategic options, perhaps the most of any game I have come across. For the most part, the strategic options are implemented much as in any game, and do not pose a particular challenge for the solitaire gamer. The one exception may be the decision of the defensive manager to either employ the pitch-out or pick-off strategy with a runner on base, as these were clearly designed with head-to-head play in mind. One gamer has devised his own set of solitaire strategy charts that have been well received by other Ball Park enthusiasts (available at http://geocities.com/gertmarriott/ or the Delphi Forum dedicated to the game at http://forums.delphiforums.com/ballparkbb).

The quality of the game components is quite good in Ball Park, with cards printed on card stock that is as heavy, or heavier, than other games, and each team has its own card stock color (there is some, mostly imperceptible, variation in card stock weight from team to team, a result of the need to use a different color or shade of card stock for so many different teams). Each park chart is printed on one letter sized sheet of card stock, front and back.

For non-DH leagues, each pitcher has an individual batting card. Moreover, players who move between leagues during the season are carded separately, if they play enough to qualify in both leagues. Pitchers must pitch a minimum of 29.2 innings in at least one league in order to receive a card. The requirement that players qualify in each league separately suggests that the cards are adjusted separately by NL and AL averages. This method makes sense, especially for pre-interleague play, but can occasionally lead to some key players not getting carded, such as Bob Wickman in 2006, who led both the Indians and Braves in saves but did not pitch more than 28 innings in any one league. The coverage of position players is very good. The criteria for whether a position player receives a card appear to depend on team roster size and on the number of games in which a player appeared rather than number of at bats. For instance, for the 2006 Yankees, Andy Cannizaro (13 games/8 ABs) received a card, but Kevin Reese (10 games/12 Abs) and Terrence Long (12 games/36 ABs) did not.

For non-DH leagues, each pitcher has an individual batting card. Moreover, players who move between leagues during the season are carded separately, if they play enough to qualify in both leagues. Pitchers must pitch a minimum of 29.2 innings in at least one league in order to receive a card. The requirement that players qualify in each league separately suggests that the cards are adjusted separately by NL and AL averages. This method makes sense, especially for pre-interleague play, but can occasionally lead to some key players not getting carded, such as Bob Wickman in 2006, who led both the Indians and Braves in saves but did not pitch more than 28 innings in any one league. The coverage of position players is very good. The criteria for whether a position player receives a card appear to depend on team roster size and on the number of games in which a player appeared rather than number of at bats. For instance, for the 2006 Yankees, Andy Cannizaro (13 games/8 ABs) received a card, but Kevin Reese (10 games/12 Abs) and Terrence Long (12 games/36 ABs) did not.

Ball Park is not an unduly difficult game to learn, especially for experienced gamers. Some may find, however, that it has a slightly more gradual learning curve than most games. Mr. Sidman includes instructions for “playing the first few games,” which allow gamers to ease into the game and gradually add complexity. At 33 pages, the playbook for the game can be a little daunting. Nevertheless, the playbook need not be read cover-to-cover in order to start playing. In fact, if one follows the instructions for easing into the game, the playbook is not used at all initially. And even when playing the full version, only a few parts of the playbook are regularly referenced during a game, primarily the section covering runner advancement.

It typically takes a couple of games to get comfortable with the base running system and to memorize what all the symbols on the cards mean. Unfortunately, there is nothing, such as the use of different font, to distinguish the results that require a park chart reference from those which are read directly off the cards. There are only seven such park chart results, so they are rather quickly memorized. The full complements of strategic options are best introduced only after one has become sufficiently familiar with the game mechanics. And once one is comfortable with the game mechanics, Ball Park does play relatively quickly and smoothly. A game typically can be completed in about 30-40 minutes.

My own experience, and that of other gamers, has shown that Ball Park is a game that rewards repeated play. The many nuances built into the game may not be apparent to the gamer at first. These reveal themselves more and more as one gains experience with the game. It is precisely these nuances in design, as well as the varied, detailed and accurate results, that keep each game with Ball Park fresh and interesting, even after dozens of games. Along with the many visual results, such as a sharply hit single, a tapper to a charging third baseman or a short fly that threatens to fall in for a Texas League single, Ball Park yields just enough unusual, or wild, plays to lend each game its own ‘personality’ without compromising playability or realism.

Ball Park may lack some of the ‘chrome' of other games. With Ball Park, you will not get a home run hit into Bernie’s Mug at Miller Park, nor will you be able to tell the number of feet that a home run traveled. Ball Park does not have explicit, variable weather effects, and umpires play no role in the game. However, I have found that what keeps me coming back to this game is the unusually rich and authentic baseball gaming experience it provides. Like picking up a good novel, I usually find myself completely engrossed in a game after just a couple of innings.

Ball Park has me playing baseball well into the off-season, and that is something I have never done before.

Excerpts from a interview with Charles Sidman

Erik Scherpf, The Sports Games Journal, March/April 2007

Reprinted with permission

Erik wrote a review of Ball Park Baseball in the last issue. Ball Park Baseball is a tabletop simulation developed in the late 1950s by Charles Sidman, now a retired professor, with input from some of his colleagues at Kansas University and, later, according to Mr. Sidman, even from baseball numbers guru Bill James (by his own account, James would play Ball Park in a Lawrence, Kansas establishment named after the game).

My wife (Margi) planted the seed that bore fruit in Ball Park Baseball when we were in Europe in 1957. She was concerned about my absorption in academic research to the exclusion of any time for relaxation and wondered whether there was not some enjoyable activity that could be pursued as an avocation. Baseball had always been a game that I found attractive because of its inherently cerebral nature and rich statistical basis.

The commitment was made then and there to develop a baseball table game whose simulation most nearly replicated the game as it was played on the field, and to use major league baseball teams and parks as the centerpiece of the enterprise. As well, I wanted also to instill an atmosphere of excitement in the unfolding plays in my game so that those who played it could easily picture themselves as managers on the field of a “real” game.

The game was first played over the Easter season in spring 1959 in the cottage that was then home just outside Madison, Wisconsin. The format was a brothers’ tournament. The game, at this time, was basic and unsophisticated, something I have come to appreciate better in retrospect. It underwent rapid revision, however, so that when the relocation to Lawrence, Kansas, took place in May 1960 it was ready for an even bigger test.

Colleagues at the University of Kansas quickly discovered Ball Park Baseball and, after playing a few introductory games, encouraged me to establish a managerial competition, with players’ being selected in an annual draft from a given league season. That league has played continuously now into its 47th year, with one original member still among its number (and with almost all of its other players long-time members of the group). It was during this early phase of my career in Kansas that I went to work seriously in newspapers. From all of the major league cities, information about various batter and pitcher tendencies going back to 1901 was transcribed onto sheets of paper for every player and every year. (for instance, where the batter hit the ball against left and right-handed pitchers and whether on the ground or in the air). Where else was that and much other information to be had then? The algorithms developed for the player cards soon came to reflect an array of hitherto unavailable information.

What was extremely valuable for the accuracy of the game was the plethora of feedback received from fellow players, who frequently interrupted my play on those Monday nights that were and are reserved for baseball in that group, but which enabled me over time to enrich the Play Book to a greater degree than what my avid yet idiosyncratic viewing of games in person and on television brought to those fascinating and unusual (but, in their carefully gauged occurrences, realistic) outcomes that gamers recognize as a hallmark of the game. Trial and error, and a willingness to make corrections over and over again, account in large measure for the near seamless accuracy of the runners advancing tables, for example. The final major changes came late in my career at the University of Florida when the algorithms for the cards and parks were put on the computer (in some 15,000 lines of code), a four year, on average three nights a week, commitment with a computer programmer par excellence whose assistance, in the last 14 years, has made possible yet additional enhancements that otherwise would not have been possible.

Ball Park Baseball became increasingly popular during the 1960s within the circle of its Lawrence, Kansas, home ground. As well, word of the game spread to constituencies far removed from the place where it was first played seriously and regularly in an organized way as individuals were accommodated with game parts for the play of what had been copyrighted as Ball Park Baseball. Late in the 1960s, after I had returned from a one-and-one-half year academic teaching and research stay in Europe, the decision was made to provide a public venue for the game. That decision resulted in the establishment in Lawrence of a baseball-themed restaurant in a building constructed for that purpose. What made the restaurant unique was the availability of baseball teams and parks, initially with most but not all pennant winners included, and some but certainly not a majority of major league seasons, for the play of the game on site. The restaurant (named “The Ball Park”) and Ball Park Baseball location opened for business in the spring of 1971.

A number of colleagues, most of them academics, joined me in the hard work of bringing Ball Park Baseball to the notice of this larger audience. They became minority stockholders in the enterprise and made significant contributions to it. The march of my academic career then intervened, as I became chairman of the Department of History at KU and active in an even more demanding way in my profession, both nationally and internationally. What had to be sacrificed was direct and intimate management of the game and business. Thus, my colleagues assumed control of the business with my approval. When in the late 1970s “The Ball Park” lease came up for renewal, they decided to discontinue that time-consuming obligation, concentrating instead on selling the game to customers who responded to their advertisements. My role at this point in time was entirely passive, the more so when I moved to Gainesville, Florida, in 1978 to become Dean of the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences at the University of Florida. In the meanwhile, in the absence of my physical presence in Lawrence, the entrepreneurial activity of my colleagues eventually flagged. As I neared retirement, the urge to re-engage with the game became ever stronger. My brother and I then took the initiative to buy out all of the many minority stockholders upon my resolve to make those improvements in the game that Bill James had brought to my attention indirectly in one of his publications, and which I later discussed with him at a luncheon in Lawrence. That initiative bore fruit and shortly thereafter I set to work with a computer specialist to hone the algorithms and to introduce those final, significant changes in the game that are now so important to its success as a baseball table game like no other in its accuracy and realism. The rest of the story resides in the game itself and the pleasure it gives those who love game simulations of real life that are the next best thing to being there and doing that.